No Strings attached ... to SQL columns

Strings are a difficult data type in database management systems. They come with variable sizes, considerable memory footprints, and incur high I/O costs. To mitigate these performance penalties, String Dictionary Encoding (DE) is frequently employed.

In simple terms, Dictionary Encoding replaces long, repetitive strings with compact integer IDs, storing the unique strings just once in a separate lookup table.

In this post, I will discuss the challenges of string management in modern databases and present a PoC developed for MonetDB that aims to solve these issues transparently.

Main Takeaways:

- The Problem: Most DBMSs duplicate strings millions of times, wasting storage and I/O.

- The Fix: Manual normalization (like MediaWiki’s

commenttable) saves space but adds massive engineering complexity. - The Solution: A new

USTRtype for MonetDB that handles dictionary encoding transparently. - The Result: up to 30x faster string operations, storage space cut in half, and zero application changes.

The Struggle: MediaWiki Pre-2017

To understand the magnitude of string data challenges, let’s look at MediaWiki, the software engine behind Wikipedia.

For years, MediaWiki used a “denormalised” schema. Every time an editor saved a change, a new row was created in the revision table. Along with the content changelog, the editor provided an edit summary (stored in rev_comment) and their username (stored in rev_user_text).

rev_id |

rev_user |

rev_user_text |

rev_comment |

|---|---|---|---|

10245 |

45 |

"WikiExpert_99" |

"fixed a typo in the intro" |

10246 |

92 |

"Editor_X" |

"revert vandalism" |

With identical strings like "fixed a typo" or "revert vandalism" appearing millions of times across billions of revisions, this redundancy was a massive issue. It bloated the database size by terabytes and filled the IO cache with duplicate bytes.

Standard String Handling & Its Inefficiencies

To understand why we need better solutions, we first need to look at how database engines handle strings.

MediaWiki typically runs on MariaDB using the InnoDB storage engine. Short strings are stored within the 16KB data page, while larger ones spill over into separate “overflow pages” on disk.

If 1,000 rows contain the string “fix typo”, InnoDB physically stores that string 1,000 times. This wastes massive amounts of buffer pool (RAM) memory, as identical bytes are loaded over and over again.

The Design Trade-off

This lack of de-duplication is a deliberate design choice to prioritise insertion speed and is a common trade-off in database design.

To de-duplicate strings on the fly, the database would need to check every single insert against all existing strings to see if it already exists. This would require an expensive index lookup or hash calculation for every row, affecting write performance.

So, databases default to “write it all down fast” and leave the redundancy problem to the user.

This approach creates several inefficiencies:

- No De-duplication: Strings are often not de-duplicated to keep insertion speeds high. Without dictionary encoding, the database would store the string “fix typo” millions of times, wasting gigabytes of storage for identical bytes.

- Expensive Equality Operations: To find the most common edit summaries (

GROUP BY summary), the database must compare the actual string bytes for every single revision, which is significantly slower than comparing integers. - Independent Storage: Even if a database compresses strings internally, they are typically stored independently per table (or even per row). Joining two tables on a string column (

revision.summary = other.summary) requires comparing the actual string bytes, not efficient integer IDs.

The Fix: Explicit Dictionary Encoding

After 2017, MediaWiki began a massive multi-year refactoring project (Actor Migration). The goal was to move from this denormalised model to a normalised model.

In the context of this migration, they split these repetitive strings into their own tables: comment (for edit summaries) and actor (for user identities).

This is how Dictionary Encoding was applied to revision comments:

Table: revision (The Main Table)

| Field | Type | Data Example |

|---|---|---|

rev_id |

INT |

10245 |

rev_actor |

BIGINT |

802 (Pointer to dictionary) |

rev_comment_id |

BIGINT |

5501 (Pointer to dictionary) |

Table: comment (The Dictionary)

| Field | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

comment_id |

BIGINT |

Primary Key. |

comment_hash |

INT |

A CRC32 hash of the text for O(1) lookups. |

comment_text |

BLOB |

The actual unique string stored once. |

The Benefits

This shift was highly effective:

- Storage Reduction: The

revisiontable shrank by terabytes. - Hot Data: Primary indexes became smaller, allowing more recent revisions to fit entirely in RAM (InnoDB Buffer Pool).

So, problem solved? Not quite. This solution came with a massive engineering cost.

Normalisation Is Good, Right?

It’s crucial to distinguish between two types of normalisation happening here:

- Logical Normalisation (The

actortable): The goal is Data Integrity. This is good design. A User is an entity. They have an ID, a name, registration date, and preferences. Moving them to anactortable makes semantic sense and reduces the risk of data corruption. - Physical Optimisation (The

commenttable): The goal is Efficiency. This is pure optimisation. The text of an edit summary is not an entity. It has no attributes. It’s just a string. Thecommenttable was created solely for efficiency reasons.

Physical optimisation is not only applied to string attributes. The same applies to certain Business Keys, like URLs or Product Codes. If you have a page_views table with a url column, it makes no sense (other than for efficiency reasons) to create a urls table just to assign integer surrogate keys to URLs.

The URL is the key and should be used as such.

The Cost of Explicit Dictionary Encoding

While the MediaWiki migrations were successful, they required years of engineering effort (from 2017 to 2022 for full cleanup). Why? Because the database didn’t do it for them.

When you implement Dictionary Encoding yourself, you inherit a logical mess:

- Ingestion Logic: You can’t just

INSERTdata anymore. MediaWiki developers had to write a complexCommentStoreclass to handle the “Lookup-or-Insert” dance for every single edit:- Select: Query

commentto see if(hash, text)already exists. - Cache Hit: If found, return the ID.

- Cache Miss: If not, insert the new string and get the ID.

- Race Conditions: Handle the case where two users insert “fix typo” at the exact same millisecond.

- Select: Query

-

Migration Pain: They had to write “Write-Both” logic (writing to both old and new columns) for years to ensure backward compatibility and safety during the transition.

-

Query Complexity: Simple reports now require joins. To find the most common edit summaries per user, you must join

revisionwithcomment.SELECT a.actor_name, c.comment_text, COUNT(*) AS count FROM revision r JOIN actor a ON r.rev_actor = a.actor_id JOIN comment c ON r.rev_comment_id = c.comment_id GROUP BY a.actor_name, c.comment_text ORDER BY count DESC;Instead of the natural:

SELECT a.actor_name, r.rev_comment, COUNT(*) AS count FROM revision r JOIN actor a ON r.rev_actor = a.actor_id GROUP BY a.actor_name, r.rev_comment ORDER BY count DESC;The second query shows the ideal scenario: Keep logical normalisation, but skip the physical optimisation hacks.

The

actortable is kept because users are distinct entities (Logical Normalisation), but thecommenttable is gone because edit summaries are just attributes (Physical Optimisation). If only the DBMS could help us achieve this…

Dear DBMS, It’s You Who Needs Integers. We Need Strings

The core problem with the MediaWiki example is that the DBMS forced the user to do the optimisation work. Developers had to redesign their schema, write complex application logic, and manage data integrity manually, just to make strings efficient.

This shouldn’t be the user’s job. The DBMS should handle string efficiency natively.

An ideal Dictionary Encoding solution would be:

- Invisible: You define a column as

TEXTorVARCHAR, and it just works. Nocomment_idcolumns, no join tables, no schema changes. - Global: A single, per-database dictionary where the same string always has the same ID.

- Efficient: Zero string duplication and all equality-based operations (

JOIN,GROUP BY,UNION, point filters) should never touch the actual string bytes. Even inequality operations (ORDER BY, range filters) should be optimised.

Implementation in MonetDB: The USTR Type

After years of performing these same manual string optimisations myself—creating dictionary tables, managing keys, and debugging race conditions—I decided I wanted to check the feasibility of that “utopian” goal of a native Dictionary Encoding. I said to myself: “It won’t work, but let’s try, just for fun.”

I chose MonetDB for this experiment because of my many years of experience with its codebase. Like MariaDB, MonetDB standard strings face similar storage issues (it manages strings using a fixed-size column of offsets pointing to a large, separate memory heap which only performs a partial and opportunistic de-duplication).

So, I built a PoC that introduces a new USTR data type.

How It Works

MonetDB allows us to create user-defined types (UDTs).

In this case, the SQL USTR data type is backed by the corresponding ustr atom definition:

CREATE TYPE USTR external name ustr;

The atom ustr is completely defined by the following structure:

mel_atom ustr_init_atom = {

.name = "ustr", // atom name

.basetype = "lng", // storage type (long integer)

.size = sizeof(lng), // size of the atom

.null = ustrNull, // null value

.cmp = ustrCmp, // comparison function

.eq = ustrEq, // equality function

.fromstr = ustrFromStr, // function to convert from string

.tostr = ustrToStr, // function to convert to string

};

Crucially, it is not stored as a variable-size type, but as a 64-bit integer ID. This ID points to a dictionary of strings that is global to the database.

typedef uint64_t ustr;

The Dictionary and Its Primitives

I’m not covering the actual dictionary implementation here, but as you can imagine it boils down to a string vector with a hash table on top of it to speed up lookups. No matter how you implement it, two primitives are strictly needed to interact with the dictionary: one to look up a string by ID and one to look up an ID by string.

char *sd_str_from_id(StringDict *sd, const ustr id);

ustr sd_id_from_str(StringDict *sd, const char *s);

When a string is inserted into a table with a USTR column, the DBMS looks up the string in the global dictionary.

If the string is not found, it is added to the dictionary and a new ID is assigned to it. If the string is found, the corresponding ID is used.

CREATE TABLE t (s USTR);

INSERT INTO t VALUES(‘Hello’);

Conversely, when a string is selected from a table with a USTR column, the DBMS looks up the ID in the global dictionary and returns the corresponding string.

As one can imagine, the global dictionary can become a bottleneck. Making these two primitives fast and scalable is crucial.

It is also important to note that the dictionary itself is immutable. Strings are never updated or deleted from the dictionary (unused strings could be removed by a background vacuum process, but I did not implement this in the PoC).

If you update a row: UPDATE t SET s='World' WHERE s='Hello', the engine simply looks up 'World', gets its ID (say, 2), and updates the integer column in the table. The string 'Hello' remains in the dictionary at ID 1, in case other rows still refer to it (no reference counts are kept, it would be too expensive).

The Fastest String Is an Integer

Even if those two core primitives are extremely fast, the primary source of efficiency for the ustr atom comes from avoiding the global dictionary as much as possible.

In other words, to stay in the realm of 64bit integers as long as possible, and only touch strings when strictly necessary.

The most direct example of this is the ustrEq function:

bool ustrEq(const void *a, const void *b) {

return *(ustr*)a == *(ustr*)b;

}

Remember that ustr is defined as uint64_t, which makes this a straightforward and very efficient 64bit comparison.

This is precisely the ultimate goal of a global dictionary. Equal strings have equal IDs. Therefore, we never need to compare strings like the standard string data type does.

First Byte Inlining (FBI)

What about the ustrCmp function, used for comparing two strings based on the lexicographic order?

This is used by operations like sorting, inequality filters, merge join implementation, etc.

If our IDs were guaranteed to follow the same order as the strings they represent, we could just compare the IDs. But this is not the case. It’s not a matter of implementation, but a matter of mathematics.

It would seem that we cannot escape a full string comparison unless they are equal:

int ustrCmp(const void *a, const void *b) {

ustr u1 = *(ustr*)a;

ustr u2 = *(ustr*)b;

if (u1 == u2) return 0;

char *s1 = sd_str_from_id(sd, u1);

char *s2 = sd_str_from_id(sd, u2);

return strcmp(s1, s2);

}

However, are we really planning on storing 2^64 unique strings in a single database? I don’t think so.

What if we use the lowest byte of the ID to store the first byte of the string? This leaves us with enough bits to store 2^56 unique strings - more than enough for any practical purpose.

Then we can rewrite ustrCmp like this:

int ustrCmp(const void *a, const void *b) {

ustr u1 = *(ustr*)a;

ustr u2 = *(ustr*)b;

if (u1 == u2) return 0;

// If the first bytes are different, we can already decide the order

unsigned char c1 = sd_id_get_first_byte(u1);

unsigned char c2 = sd_id_get_first_byte(u2);

if (c1 < c2) return -1;

if (c1 > c2) return 1;

// Otherwise, we need to compare the strings

char *s1 = sd_str_from_id(sd, u1);

char *s2 = sd_str_from_id(sd, u2);

return strcmp(s1, s2);

}

Note that we store the first byte, not the first character (which could take multiple bytes). This is perfectly compatible with MonetDB’s internal string representation based on UTF-8 (UTF-8 maintains code-point order under binary sort).

The important optimisationhere is that sd_id_get_first_byte() never touches the global string dictionary. Extracting the first string byte from the ID is just a matter of bit manipulation.

Assuming a uniform distribution of ~100 printable ASCII characters, the probability of two strings sharing the same starting byte is roughly 1%. This means we avoid the expensive dictionary lookup 99% of the time. With Unicode, this probability drops even further, making dictionary access a rare exception.

Of course, this is a simplification. In reality, the distribution of first bytes is not uniform.

If we were to sort a set of URLs with this technique, it would not bring any benefit since all strings start with h.

Short String Inlining (SSI)

Avoiding lookups to the global dictionary is a great way to make the ustr atom efficient.

Do you know what is even more efficient? Not using the global dictionary at all.

For strings up to 7 bytes (plus at least one null terminator) we can store the string directly in the 64-bit ID. No dictionary storage needed.

For example, the string “Hello” can be stored in a 64-bit ID like this (the string is right-padded with null bytes):

0x48656c6c6f000000

H e l l o \0\0\0

This special ID (identified by the last byte being 0) does not represent an index into the global dictionary. It is the string itself.

In this case, sd_str_from_id() converts the ID to a string with a zero-cost cast:

s = (unsigned char*)&u;

The shortest inlined string is the empty string, which is encoded as 0x0000000000000000, i.e. ID number 0. Quite fitting.

The opposite, storing a short string as a ustr, is equally trivial.

Note that the IDs of inlined strings always have the highest byte set to 0. In principle, this would leave the address space for the dictionary index almost untouched, with (2^56)-1 possible indices. In the PoC, for simplicity, I avoided using the entire highest byte for the dictionary index, which leaves us with 2^48 usable indices (8 bits for FBI, 8 bits for SSI). Still more than sufficient for any practical purpose.

Short String Inlining is not a new idea, but one that fits very well with the ustr atom.

Because First Byte Inlining stores the first byte in the lowest byte of the ID, it is directly compatible with Short String Inlining.

That is, sd_id_get_first_byte() does not even need to know whether the ID is a short string or a dictionary ID.

Its effectiveness depends of course on the nature of the data, but short strings are more common than one might think, and this targeted optimisation is hard to bead.

State of the Art: Compression vs Normalisation

You might be thinking: “Wait, don’t modern columnar stores (like Snowflake, Redshift, DuckDB, MonetDB) already do Dictionary Encoding?”

Yes, they do (all to a different extent), but with a crucial difference: Scope.

Most columnar stores use Dictionary Encoding as a compression technique, applied locally per file, row-group, or “chunk”.

- In Chunk A, the string

"Apple"might be encoded as ID1. - In Chunk B, the string

"Apple"might be encoded as ID5. - In Chunk C, if

"Apple"is rare, it might not be encoded at all.

This means that while they save storage space, they do not provide a global unique ID for the string "Apple". To join Chunk A and Chunk B, the engine still has to decode the values or map them to a common temporary dictionary. Use cases like JOIN or GROUP BY cannot assume that ID(A) == ID(B) means String(A) == String(B).

The USTR type is spiritually similar to ClickHouse’s LowCardinality, but with a more fundamental ambition. While LowCardinality is an optimisation that may fall back to local dictionaries or require re-encoding during joins across tables, USTR enforces Global Normalisation as a strict invariant. It guarantees that "Apple" is ID 1024 everywhere in the database, across all tables. This allows the engine to execute complex queries entirely on integers, treating strings as first-class numeric citizens.

It is worth noting that explicit compression techniques like FSST (used by DuckDB) also primarily target storage reduction rather than execution speed through global unique IDs. However, FSST is uniquely interesting because it allows for random access to individual compressed strings (unlike block-based compression). This makes it a perfect candidate to compress the unique strings inside the global USTR dictionary to achieve even greater storage savings without sacrificing lookup performance.

Note: In the early stages of this PoC, I actually implemented a compression scheme for the dictionary strings (using Unishox2 for short strings and LZ4 for longer ones), but it was later removed because the additional storage savings did not justify the added implementation complexity and prevented some optimisations.

Results

The concept of a global dictionary immediately raises concerns about performance bottlenecks—particularly regarding insertion contention and lookup overheads. However, despite these theoretical challenges, preliminary results indicate that this approach is highly promising.

Datasets

I used two datasets for benchmarking. Both datasets are extracted from a knowledge graph about the municipality of Amsterdam.

attributes |

tokens |

|

|---|---|---|

| Description | All string attributes from the knowledge graph |

Terms from a string tokeniser |

| Total Rows | 6M | 477M |

| Unique Strings | 2.78M (46%) | 2.1M (0.44%) |

| Inlined Strings (<=7B) | 7% | 74% |

| Length (Min / Med / Avg / Max) |

1 / 91 / 1102 / 99530 | 1 / 5 / 6 / 1958 |

Storage Savings

The savings in terms of storage space that are achieved using the USTR type are:

| Dataset | STRING size |

USTR size |

Change |

|---|---|---|---|

attributes |

6.27 GB | 2.87 GB | -55.2% |

tokens |

3.48 GB | 3.56 GB | +2.3% |

Notice that even though the tokens dataset has much more duplication, USTR actually ends up using slightly more space than the standard STRING type (+2.3%).

This happens because MonetDB performs some opportunistic de-duplication on standard strings, which in this case was effective enough to allow the use of 32-bit heap offsets (4 bytes per row). USTR always uses 64-bit IDs (8 bytes per row).

Unfortunately, while standard strings save some space here, they lack the strict uniqueness guarantees required for the equality-optimization that makes USTR so fast. Furthermore, this advantage is temporary: as data grows, standard strings would eventually require 64-bit offsets, negating the saving. Finally, it is arguably more interesting to note that the full database from which these two datasets were extracted yields a 53% reduction in storage space compared to the same database using the standard STRING type.

Benchmarks

Benchmarks were run on a i9-14900T CPU with 64 GB of RAM, using MonetDB 11.55.

Tasks

COPY INTO: bulk load the dataset from a CSV file into a tableCOUNT DISTINCT: count the number of distinct strings in the tableORDER BY: order the rows of the table by the string columnJOIN: join the table on string against a 1K sample of itselfJOIN (hot): the same join a second time (hash tables should be available)

Results

| Operation | attributes (STRING) |

attributes (USTR) |

tokens (STRING) |

tokens (USTR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

COPY INTO |

26.19s | 21.91s | 37.44s | 30.93s |

COUNT DISTINCT |

7.52s | 0.25s | 17.21s | 8.70s |

ORDER BY |

15.56s | 5.91s | 134.00s | 91.00s |

JOIN |

7.73s | 0.36s | 57.52s | 46.77s |

JOIN (hot) |

0.041s | 0.039s | 39.04s | 38.78s |

Although the two datasets show different behaviours due to their different distributions, the USTR type is always faster.

The bulk load improvement can be attributed to the lower amount of I/O required to store the strings.

The massive improvement in COUNT DISTINCT is due to the grouping operation being performed entirely on integer values, with no string ever touched.

The ORDER BY improvements are mainly due to First Byte Inlining, which allows the comparison to be performed on integer values in most cases.

The JOIN improvements are admittedly less dramatic than expected. This is primarily due to the exceptional optimisation of string joins in MonetDB. While USTR provides a faster integer-based join (as evidenced by the hash table creation speed), the standard string implementation is highly competitive.

Concurrency

A global dictionary creates a single point of contention, which can be a bottleneck in highly concurrent environments.

I will not go into much detail, but the extent of my effort in this direction boils down to the following few points.

The dictionary can be accessed only through the two primitives seen above, which simplifies dictionary lock management. It is imperative to keep locks for as short as possible, in particular for the write lock. It pays off to invest time in an optimistic lookup, with either no lock at all, or with a read lock. Only when the lookup fails is a write lock necessary.

It helps to keep a small staging area where new entries are collected, and periodically flushed to the main dictionary in a single batch. This optimises I/O and minimises lock contention.

Dictionary sharding greatly reduces contention. Given a set of N shards, each string goes to a shard based on hash(string) % N.

This way, the chances of concurrent access to the same shard are reduced by a factor of N.

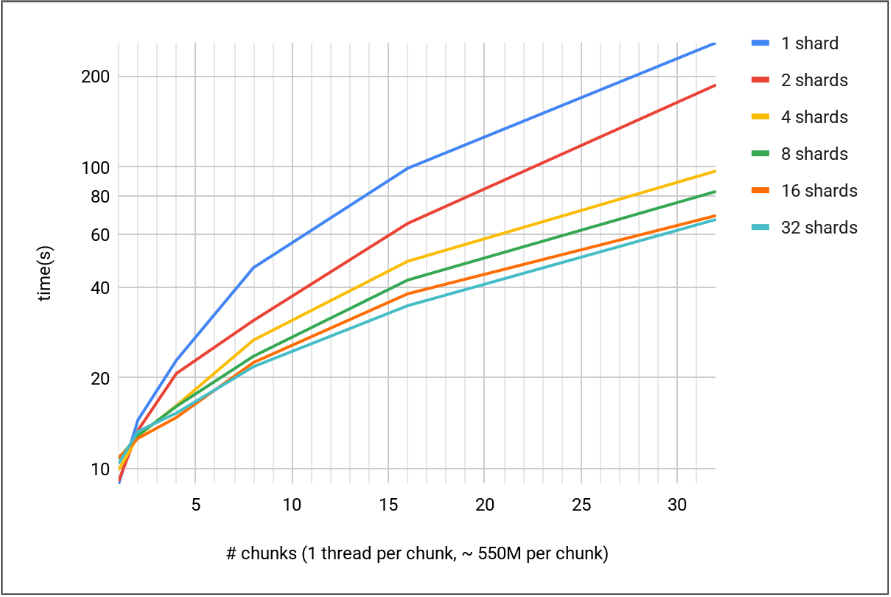

I have performed a concurrency test with the USTR type on a dataset similar to tokens (see above), but larger (1.6B rows, 112M unique strings, 28% inlined).

The test performs a parallel bulk-load of equally-sized chunks of the dataset.

Each chunk is loaded in parallel by a different thread.

Notice that this is the most stressful test for concurrency, as all threads are 100% busy with trying to access the dictionary, potentially in write mode.

This plot shows the performance of the parallel bulk-load in relation to the number of shards used for the dictionary:

Distributing the workload across more shards effectively reduces contention, leading to significant performance gains as concurrency increases. This advantage becomes clear as soon as 2 or more threads are used, which suggests minimal overhead from the sharding itself.

PoC Status and Future Work

Both the PoC and the benchmarks are far from exhaustive work, but they are a good indication of the potential of this approach.

Several challenges and improvement directions remain, such as:

- Efficient integration with common string functions, operators, and indices

- Dynamic sharding

- Efficiency improvements for the “unlucky”

USTRcases (e.g., sets of strings sharing the same first byte) - Expansion of the dictionary to centrally store common string statistics, to support all of the above

- Vacuuming the dictionary to reclaim space from deleted strings (offline operation? background thread?)

Will we soon be able to freely use strings in our favourite SQL DBMS without paying the price? I certainly hope so.

I suggest keeping an eye on future MonetDB releases.